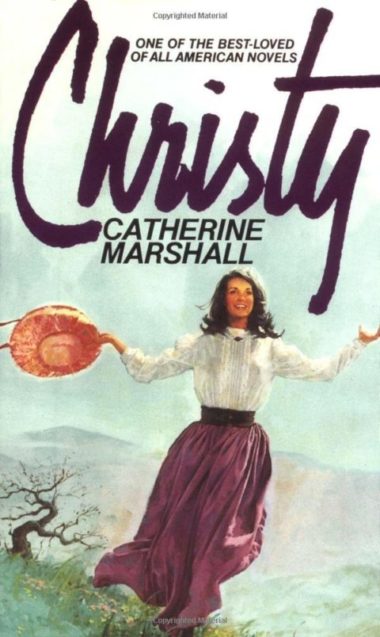

I guess you could say I have a passion for history and a passion for people. Perhaps that’s why I felt so connected when I stepped into the world of real-life missionary, Opal Myers. My fascination began years ago with a story. It was in late summer of 1971 when I first read Christy, the 1968 national bestseller by Catherine Marshall. The book was based on the life of Catherine’s mother, Leonora Whitaker Wood, who, according to the book, in 1912, at the age of nineteen, left the comfortable home of her parents in Asheville, North Carolina, to become a teacher at a mission in Cutter Gap, an impoverished back mountain area of eastern Tennessee.

In the book, Christy (Leonora) struggles with the harsh realities of the poverty-stricken community but is determined to improve the lives and education of the children. She is encouraged and challenged through the mentoring of Miss Alice, while caught in a love triangle with John Wood, the mission preacher, and Dr. Neil MacNeill.

Once I started the book, it was almost impossible to put it down. I was absolutely magnetized by the story, the proud mountain people, the way of life with its everyday human struggles, and the courageous mission workers. Catherine Marshall painted a vivid picture of the cove with all of its poverty and smells! I was in awe of Christy, young and pretty, innocent and naive, confused by her romantic feelings for the preacher and the doctor, but all the while tenaciously dedicated to the well-being and education of her students and their families.

At the time I read Christy, I was living in Greenville, South Carolina, not all that far from where the story took place. I couldn’t help but wonder if maybe, even after sixty years had passed, there might be some evidence left of the mission’s existence.

The real names of the towns had not been used in the book, but there were enough clues to narrow down the location, especially with the map in the front of my copy of Christy. If the general layout of the towns were the same in conjunction with the French Broad River, I felt we could certainly get close to where the mission had been and then we could ask the locals for more specific directions. I compared the map in the book with a road map of that area. The French Broad River and the railroad tracks coming from Asheville seemed to match up, and there was a small town with a Spanish name next to the railroad tracks no more than ten or fifteen miles into Tennessee. Could Del Rio possibly be the same town as Christy’s El Pano?

It would be an adventure to solve the mystery of its location and I was fairly certain that we could find this Cutter Gap no matter how remote it was. I was determined to at least give it a good try.

Manly, my husband, Matthew, my son (four at the time), and I twisted around most of the winding Cocke County back mountain roads outside of Del Rio. On our second day of exploring, we stopped at a little country store, a slightly modern version of the stores of the late 1800s. Several men idly sat around a cold, potbellied stove, chewing large tobacco cuds while spinning their yarns, frequently spitting into a box of sand, usually hitting their target.

The lady behind the cash register said she could give us the exact directions to the mission location. “Ya go down yonder a spell and turn back thataway ‘n cross back o’er the crick. After ya go quite a spell, take the rat fork. Ya can’t miss hit, budhit ain’t thar no more.”

Well, after we “turned back thataway” and had “gone a spell,” we bumped along one of the roughest, if not the roughest, roads in all of Tennessee. It was like driving on a washboard. In some places, four to six-inch-deep gullies of running water streamed across the road, and where there were bridges, they were rickety and scary to cross. In other places, big chunks of dirt and gravel had broken out of the edge of the road and fallen down the mountainside, leaving large semicircle gaps in the already narrow road. In fact, the road was so narrow in many places that it was not wide enough for two cars to pass each other. When we took the right fork, the road immediately narrowed down to one lane. That single lane soon became two ruts with grass growing in the middle.

At a big curve, the road ended and became what looked like an overgrown trail. Hidden within that curve, back off the road a few hundred feet, a little white house was guarded by an overgrowth of vegetation. Animals scampered off the footpaths as we walked toward the house. The modest home itself seemed to be encircled by barnyard animals: a mule, a few pigs, and several dogs, while the roosters, hens, and baby chicks were everywhere. A sun-kissed lady came out to greet us and it was obvious she was thrilled to have company. I’m quite sure she didn’t have many people dropping in on her, and she was eager to do everything possible to encourage us to stay around a little longer.

She enthusiastically told us all we wanted to know about the old Ebenezer Mission. “Opal Myers owns all that mission land up thar.” She extended a weathered hand. “Lived in the old mission house too ’till hit burned down in ’62. Burned down to the ground, hit did. Nutt’n left now but some ol’ foundation stones. Miss Opal’s livin’ out, down thar in Slab Town now. Thar’s still a few cabins a standin’ ‘n maybe a barn or two.”

She then offered to take us the rest of the way to the mission on foot. “Hit’s a mighty grown up up thar, but I reckon we can find some of them foundation stones. That young’un of your’n thar can ride on my mule.” Of course, Matt loved that!

We walked through knee to hip high grass all the way up to where the mission had once stood. There was still a crumbling rock wall and a foundation of stone peeking through the weeds. Looking around, I wondered what it would have been like to be standing in that exact spot half a century earlier.

In 1972, we moved from Greenville, South Carolina, to Savannah, Georgia, where we added two new members to our family: Jonathan, our son, who was born in 1975, and an Alaskan malamute named Tosha. Our work, activities, and the distance did not make it possible for us to return to the mission for some time.

In 1976, Manly, who then worked for General Electric, was transferred to Atlanta. We purchased an old Victorian house in Jefferson, Georgia, about an hour north of Atlanta. We were much closer, but restoring the house and our involvement as senior high youth counselors at the United Methodist Church consumed all of our free time.

It wasn’t until ‘77 or ‘78 that we went back to the mission. As we turned off Hwy 107 onto the Old Fifteenth, it was as if time never touched the place. Everything looked just as I had remembered it: washboard roads, rivulets of water trickling from one side of the road to the other, places where the edge of the road had fallen down the mountainside. Going down the road by Sand Hill were the huge washed-out gullies which crisscrossed the road a couple times at the bottom.

The only noticeable change was in that last fourth of a mile to the mission property—the road was now scraped and covered with a dusting of gravel. However, it was still only one lane, narrow and rough with washouts and ruts. In one place, a spring produced a trail of water flowing from one side of the road to the other. As we passed the mission’s foundation, there were two places where large rocks protruded from the middle of the road, giving us the option of carefully navigating around them or scraping the bottom of our car and possibly removing our exhaust system.

As we pulled up to the old log cabin at the end of the road, Opal came out to greet us and immediately made us feel welcome. Opal spoke quickly, moving without hesitation from one subject to another, from the past to the future, and then back again to the past, many times answering our questions before we had even asked them. It was as though she had been waiting years for our arrival and now here we were. All the things she had been saving up to tell us couldn’t wait to spill out. Opal was like this with all who visited her. She loved people—loved being around them—and in return everyone who met Opal loved her. Since our last visit, there had been many others who had fallen in love with Christy and found their way to the mission.

Opal told us how her parents had moved to the mission community in 1915, living on a portion of property owned by her grandparents. Her sister Maggie started attending the mission school with Opal’s Aunt Flora. Opal started school at the mission in 1919 at the age of eight. In 1944, she had purchased the mission property and later acquired some adjoining parcels of land which gave her a total of one hundred and eighty acres, including all of the mission land plus the home sites of many of those who had lived around the mission.

We continued coming back two or three times every year. Being the hardy crew we were, “roughing it” at Opal’s was always a great adventure. Our tents were comfortable enough for a good night’s sleep. Even as late as the 80s and 90s, indoor plumbing and running water were considered a luxury back in the cove where Opal lived, so we bathed and washed our hair in the “swimming hole” of a close-by mountain stream. That stream was always frigid, even on the hottest days in July and August, but Matt and Tosha never seemed to mind that. To this day I chuckle when I remember the time Manly carried Jonathan across that stream, carefully moving from one rock to the next. A slippery rock caught him off-guard, sending them both into the icy water.

Opal’s grandsons, Barry and Benja, lived with her and Matt enjoyed playing with them while Tosha preferred sniffing out the pigs. Benja would take the go-cart he had made up the side of the huge hill behind the house and heedlessly fly down that mountainside, nearly scaring me to death; when Matt decided to drive it I nearly had a coronary.

Opal’s house was much like those described in Christy. The holes in the screens were an invitation to every fly that hovered over the chicken yard, and that chicken yard came right up to the entrance to her cabin. In fact, it was not uncommon for the chickens and roosters to perch on the porch just outside the door, sometimes finding their way right into the cabin.

We would always bring food to cook over a campfire or on our camp stove, but most of our meals we ate with Opal; she always insisted. Opal had two stoves in her kitchen—a wood burning stove by the door as you came into the cabin and an electric stove at the other end of the kitchen where she cooked. In all those years, I only saw Opal cook on one temperature: HIGH. Her handmade biscuits and mud pudding will always be a part of our memories, as will the curly strips of flypaper that hung suspended over the table, only slightly above eye level, as we sat there eating. The strips were usually already well covered with flies, half of them still buzzing, with maybe enough room left on the sticky surface for the flies that we had just shooed off our food.

After dinner, we would wash the dishes in water that had been carried up from the spring and heated in big pans on the wood burning stove. Oh, and visiting the outhouse was ALWAYS a thrill!

Yes, it was like going back in time to the days of Christy. But I can tell you for a fact that I would not trade a moment of my time with Opal to be the guest of honor in the palace of a king. Being in Opal’s presence and hearing the stories of the past was purely fascinating.

We spent hours talking with Opal about the old days, sometimes relaxing around her kitchen table, other times walking, exploring the long deserted home sites of the early 1900s in what is now the Cherokee National Forest. Opal wore her customary hat when we went walking and was never without a walking stick.

In the national forest, she pointed out the Christmas fern and explained how it got its name. She talked about arbutus and other plants and their uses. On one memorable hike, we walked down across the field towards where her grandparents had lived and she instructed me in the art of naturally repelling insects as she carefully selected plants and stuck the ends of them under her hat. This, she explained, would keep the pestering gnats and other insects away, and it did.

Opal talked about the past and history breathed life as we walked about together in the cove. She recounted how Morgan Branch and Morgan Gap got their name from Morgan’s Raiders during the Civil War.

Back in the 30s and 40s, many of the young men in the community traveled to surrounding states, especially North and South Carolina, to work in the mills while others went north to work in the factories or in coal mines. Many of them sent their paychecks back home to help support the family they left behind. We found evidence of this as we explored deserted old cabins. In one we found boxes of clothes, some of which had been torn open and flung about the floor along with other old papers and letters. Among the papers were pay stubs from cotton mills in the Carolinas.

Sometimes we went exploring on our own, taking long walks over to the next ridge or taking the steep trail down through Morgan Gap to where the railroad tracks followed the twists and turns of the French Broad River. It was there, years before, that Opal’s father had caught the train at the West Myers whistle stop to ride into Newport with crops to barter for needed supplies. The three miles down to the river were always much easier than the same three-mile climb on the way back.

As Matt and Jonathan got older, Matt didn’t come with us as often, but Jonathan still enjoyed our “trips back in time.” He loved to swing out over the banks on rope swings and vines and to start our campfires while Heather (born in 1981) preferred helping Opal make biscuits and mud pudding. She even made sure her handprint and initials were permanently placed in the wet cement chinking on the backside of the new log outhouse. We all loved going to church with Opal. Sometimes Opal would let Jonathan or Heather help ring the church bell. It was understood in the small congregation that nobody rang the church bell except Opal. Even after she became very ill and no longer had the strength, even then they would always ask her permission before letting someone else ring the bell. We could tell that she was well loved and respected by everyone in the community.

Opal had always dreamed of writing stories about the mountains and her people, but it didn’t quite happen as she imagined. Instead, the Lord sent Catherine Marshall to write the story of her mother Leonora and the mission school. Catherine started researching and writing Christy probably around 1957. In 1959, she came with her mother and father to visit the mission. All the old church and school records Opal had saved fascinated Catherine. Some of these records included bartering transactions between the families and the mission to pay the mission school’s tuition. These were only some of the treasures that were lost when the mission house burned. Mrs. Wilford Metcalf and others in the community also furnished Catherine with information about the area. Opal later met and became friends with Catherine’s sister and they corresponded. Opal let me read some of her letters.

Opal treasured the book Christy, but far more than the fiction of Christy, she loved the true story of the mission. In her own copy of the book, on the pages listing the characters, Opal had written the name of each local person that character was based upon. She had made additional comments on other pages of her book, which I also copied.

It was one of her greatest hopes that one day the book Christy would be made into a movie. That hope was most likely sparked, over the years, by visits from movie producers, photographers, and location managers who came to look over the area where the story had taken place. Some spent hours talking with Opal and the photographers took numerous pictures of the area, Opal, and her grandsons.

Each year, as Opal got older, she talked more and more about having her family history written. She was concerned that the past would be forgotten and the family and local history would become distorted. It was very important to Opal that her granddaughter Lori have an accurate copy of this history, and that she, in turn, would pass on to her children the stories and strong heritage of their ancestors.

Even though I knew she wanted me to write her family history, I didn’t volunteer to do so. I felt much too inadequate to take on such a task. I was convinced that someone better qualified than I, a “real” writer; a genuine published author would come along and be absolutely thrilled to embrace such an opportunity. After all, there were hundreds of people who had searched for and found the mission, as we had. There were doctors, lawyers, teachers, and even that movie producer, so surely a writer would come to record and tell the incredible story of this extraordinary mountain woman and her family. But, no one came and when Opal’s health started to fail, she became more insistent.

In 1989, she asked me to listen to a tape she had made for Lori two years earlier. After listening to it, I agreed to write her family history and we started by making several tapes with her and some with her sons as well.

It was wonderful seeing her excitement as she relived event after event. The more I learned about Opal, the more I realized what a treasure God had given to me and to the people of this back mountain area. I diligently transcribed the tapes and put the information in chronological order. That in itself was a huge task, but simple enough. When it came to writing the story, the rough draft was easy, but putting it into its final form seemed impossible. From time to time, after Opal died in 1991, I would dig out the old files and try, but I just could not finish. How could I retell this amazing story? The story of a woman who deeply loved Ebenezer Mission and the school she attended. The story of a courageous woman, who from the time the mission formally closed up until the day she died was the mission, giving hope and encouragement to all those around her. Her life was powerful in the most simplistic way. Her life to this day shines as bright as any mission worker who ever set foot at the Ebenezer Mission. Opal deserved a Catherine Marshall to tell her story, but all she got was me. I can only hope that somehow my love for her will make the difference.